Cultural survival means resurrecting tribal thinking and the way humans thought a million years ago up to the Great Forgetting

There’s a real sense that we are past staying this mono-cultural collapse, and a book that came out 20 years ago, enlightens now more than ever, with the multiple forces of environmental, economic and societal collapses occurring under the weight of an elite and the barbarity of capitalism and extreme ecosystems and social systems exploitation.

This concept is what the subtitle suggests –

An Adventure of the Mind and Spirit. A book that ties into an earlier one,

Ishmael, where writer Daniel

Quinn gives us a gorilla with the power of human history locked up inside his brain, whereupon he communicates through the life stream of extra sensory perception.

The ideas are deep in

The Story of B: An Adventure of the Mind and Spirit, but in reality the understory of the magnificent storytelling is a simplicity that can cause anyone to pause – how it is, now in this totalitarian and singular culture of takers, those in the agency capitalism, unfathomable plundering of ecosystems, and unbridled consumerism, that more and more people are listless, brutalized by media, drugged or boozed out, looking for the pornography of emptiness, suicidal, feeling worthless, and counting on some redemption in a singular god with big G afterlife.

Leavers, as outlined in

Ishmael, are tribal people, tied to community of place and the geography of time, embedded in nature, as one community, that is, a single small species in the entire web of millions of others. Hunting and gathering is a determining process that keeps clans small – 30-ish – and people with song and stories and art and language who understand the scheme of things — a culture based on all species webbed and interconnected with everything else, each blade of grass, grub, predator, prey.

The leaving part of the leaver culture is in knowing we are one inside a natural world, an element among other elements, part of nature, not here to subdue it, tear it, control it, and wipe out all other parts of it to reign as King of the Jungle. Quinn emphasizes that the natural world, which includes “Leaver” cultures, sustains itself through what he calls the law of limited competition. Under this peace-keeping law, he says, you may not hunt down competitors or deny them food or access to it. You also may not commit genocide against your competition.

With that, and in the The Story of B, Quinn goes into a deeper history of humans, looking at the 200,000 years as Homo Sapiens, with that big shift 12,000 years ago adopting a taker thinking; i.e., agriculture. It’s something I’ve been teaching for forty years, and Quinn refines it in a book about B, first a man in Germany who meets with anyone, in theaters and out of the way places, to talk about the Great Forgetting. B (Charles) gets assassinated on a train, and his role is subsumed by a woman named Shirin, the new B. Eventually, she and others are inside a theater when a bomb goes off, survive, and then the priest is now enlisted — he disavows his Christ and his religion — to be B. But the Great Remembering clan is on the run, fearful of the forces of religion and militarism.

Jared is that Laurentian priest, given the gold master card by his boss to investigate B, which the priesthood hierarchy suspects is the AntiChrist because of his heretical teachings about human life way past the date of first town and farm. It’s a look at civilization’s greatest minds drawing humanity’s very birth from the city and farm — forgetting that we are from a lineage 4 million years old, and several hundred thousand years as Homo sapiens in that hunter and gatherer role, comprising thousands of distinct and diverse cultures. That is the antithetical nature of the story, how what we were then, for a million years or more, that those principles and ways, that we were born from that, and our humanity comes from that space and time.

To think humanity is rooted from that past into what we are now, or that we are defined by the advent of armies and machines, religions and famines, and pestilence, politics and kings, despots and consumer insanity, is to erase millions of years of history — a time that even modern thinkers see as pre-history, an insignificance, savages!

That valuable wealth of knowledge and action, those terms of human exchange and how we knew our role in nature, what nature was, how the planet was made up of millions of great brothers and sisters with fins, wings, claws and fur, it has been marginalized and demolished. Leavers were wiped out by disease, the ax, the gun, the poisons, the bombs of Taker society.

I find that this readjusting in my students, to understand what it means to be of one rotten, eating from the inside out culture, is so hard for them, almost like signs from Mars . . . and as blind as anything we as supposed thinker species could have believed, and continue to believe in our hubris of forgetting the elements of power in being and intuitive knowing our place in nature, not outside it, ready to slash and burn and pollute it into oblivion.

In

Ishmael, the gorilla says: “And only once in all the history of this planet has any species tried to live in defiance of this law — and it wasn’t an entire species, it was only one people, those I’ve named the Takers. Ten thousand years ago, this one people said, ‘No more. Man was not meant to be bound by this law,’ and they began to live in a way that flouts the law at every point.”

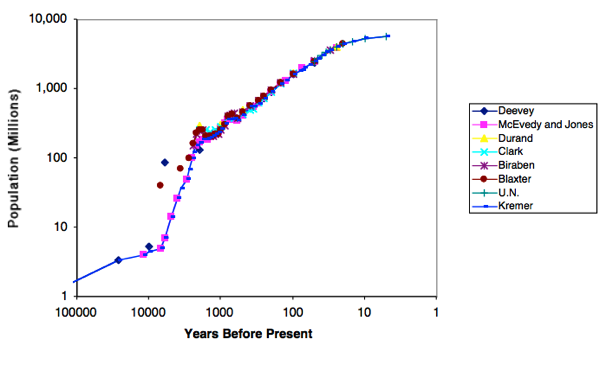

That way is totalitarian agriculture, which pushes all other species and systems to the brink of collapse in order to satisfy this Taker mentality of wiping out all competitors to satisfy a bizarre aim at growing more and more food, way past any clan’s needs. Surpluses have added to human population in incredible numbers, where for 150,000 years there probably were 10 million of us, and then, as the grain and legume were planted, civilizations sprang

Our totalitarian system is all about toiling, and famines, plagues, masters and slaves, disease, insanity, punishment, laws, politics – and B talks about the millions, tens of millions and hundreds of millions over the course of 5,000 years of history who died of starvation even as food production bulldozed more land, more water was poisoned, and bigger and uglier cities were built. Imagine, those great numbers dying in what was supposed to be the civilized cultures, without the savage tie to earth and sky, even though food growing increased and increased. Population grew along with food growing: amazing doubling of the population and doubling more and doubling and doubling, until we now have 7.1 billion, going for 9.2 billion by 2050 (or is it 11 billion?).

Famines throughout history — not beginning with the Irish potato famine of 1848, 1.5 million dead; Vietnamese of 1945, 2 million; Bengal famine of 1770, 10 million dead; Soviet famine of 1932, 10 million dead; Chalisa Famine of 1783, 11 million dead. Famines go back to Greece and Egypt and Spain and Italy . . . thousands of years ago. What accounts for this, when our population goes up and farming goes up with it?

B explains this and more in his Great Remembering talks, a way to reframe who we are, since

Homo-something (I call us today, Retailopithecus or Consumopithecus Sapiens,

here and

here). So we, thousands of cultures, Leavers, have been around for 4 million years, and we worked well in those gene pools and behavioral suits, until around 12,000 years ago.

Growing crops by clearing the land, killing the species, mucking the waters, it became a way to control people – power – and great abundance of food propelled armies and made wars and greater wars possible. But simply put, as B states in the book,

Totalitarian agriculture is based on the premise that all the food in the world belongs to us, and there is no limit whatever to what we may take for ourselves and deny to all others. (Story of B, Chapter 26, Page 260)

These ideas are those that we were supposed to talk about with youth, K12, and in college, and understanding how wrong this mono-culture is, and how we have to change our total thinking, our mindset, our emotional attitudes, to survive . . . .

According to the mythology of our culture, the world was made for Man to conquer and rule–and Man was made to conquer and rule it. Man is eminently fit for this job, and “humanizing” the world (for example, by clearing a formerly untouched habitat and putting it to the plow to produce human food) is a blessed thing to do. According to our mythology, humans represent a separate and higher order of being from the rest of the living community (which of course Christianity confirms). According to our mythology, the world is a human possession, to be used as suits us; it has no intrinsic value, no value outside the human frame of reference. Songbirds exist to provide us with musical entertainment, and if we decide we can do without that entertainment, we’re free to dispense with songbirds. Faced with a stand of trees, the only question to be asked is, “Would we rather leave it as it is and have a park or level it for a shopping mall?”

According to our mythology, we are humanity itself, and those who lived before were merely “savages” (like the Yanomami and Gebusi), which is to say, something less than human. We live the way people were “meant” to live from the beginning of time, and everyone in the world should be made to live the way we do. According to our mythology, there is one (and only one) right way for people to live, and we have it (which is why it must be imposed on all others). Because we live the way people are “meant” to live, we must cling to it even if it kills us. At the same time, according to our mythology, humans are deeply and irremediably flawed, and this accounts for the fact that so much of what we do turns out badly. The fault is not to be found in the way we live, therefore, but in human nature itself. And since we are the ONLY true representatives of humanity, we need only look at ourselves and our own history to discover what “human nature” is.

Chilling, how out of balance our species has become, and for evolutionary minds, it’s tied to farming, to the big project of plowing earth and exploding rivers and killing species to grow more and more stuff for more and more armies so fewer and fewer kings and bankers and rulers will control the masses.

For one million years before now, there were 125,000 of us, and 300,000 years before now, 1 million, and we sit on our thumbs and think that our populations can keep growing, and growing, and that technology and machines and chemicals and homogenized culture will get us out of this dilemma of many snake heads — climate change, perpetual war, environmental pollution, toxicity, unending pain and exploitation of fellow humans, and the extinction of 200 species a day.

Any culture will become an obscenity when blown up into a universal world culture to which all must belong.

— Daniel Quinn’s The Story of B: An Adventure of the Mind and Spirit, Chapter 10, Page 82

Paul Kirk Haeder has been a journalist since 1977. He's covered police, environment, planning and zoning, county and city politics, as well as working in true small town/community journalism situations in Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Mexico and beyond. He's been a part-time faculty since 1983, and as such has worked in prisons, gang-influenced programs, universities, colleges, alternative high schools, language schools, as a private contractor-writing instructor for US military in Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and Washington. A forthcoming book,

Reimagining Sanity: Voices Beyond the Echo Chamber, looks at 10 years of his writing at

Dissident Voice, and before, to bring defiance to the world that is now lobotomizing at a rate never before seen in history.

Read other articles by Paul, or

visit Paul's website.